Page Contents

OVERVIEW

How could someone ever confuse orthostatic hypotension for a pulmonary embolism? It seems unlikely that this would every happen in real life…however that is not the case! The story below explains how a simple case of orthostatic hypotension was thought to be a pulmonary embolism (and the clinical consequences of such confusion).

WHAT HAPPENED?

The patient in question is a 40 year old woman who recently underwent a breast reduction surgery 10 days before she comes into the hospital complaining of having “fainting spells”. Very quickly this patient begins a workup that includes a D-dimer lab test which comes back borderline elevated (550 ng/mL, where the cutoff used is often 500 ng/mL). Immediately after this lab result, the patient is suspected to have a pulmonary embolism (PE), and is sent off to radiology to have a CT angiogram of the chest. The results of this study show a “small segmental singular filling defect” in one of the lungs, and the diagnosis of PE is solidified for the patient.

Upon being given this diagnosis, this patient is given IV heparin to help treat the PE. The consequence of this is now that this patient (with her recent surgery) begins to bleed from her surgical sites. In addition, the patient still complains of having her same “fainting spells”. These persistent symptoms motivate the team to begin a cardiac workup (electrocardiogram and troponins). Upon these coming back unremarkable, it is decided that the patient’s condition is “non-cardiogenic”.

The next recommendation is to order a brain MRI to evaluate for pathology that could explain the patient’s symptoms. A brain MRI is ordered for the patient, and the only remarkable finding noted are low lying cerebellar tonsils (an incidental finding that does not explain her symptomatology). At this point neurology is consulted and a medical student goes to see the patient. This medical student notices that some aspects of the patient history are confusing, so he spends his time collecting a thorough history which reveals a very important element of the patient’s history. He notices that her fainting spells sound very consistent with those seen in orthostatic hypotension/vasovagal syncope (i.e. poor perfusion to the brain in an acute setting). This medical student asks the patient to stand up, at which point her heart rate jumps from 80/min to 120/min, and she complains of blurry vision, and a “warmth” coming over her.

At this point the medical student feels quite confident that some combination of orthostatic hypotension/a vasovagal response is responsible for the patient’s symptoms and communicates this with the rest of the team. He does not believe that an aggressive workup is needed at this point.

AT WHAT POINT DID THE FOREST BECOME LOST IN THE TREES?

It seems that often times in medicine we minimize the patient history and go straight to the lab tests. While it is true that a patient history can often be confusion and IS by definition subjective data, it can not be overlooked! One could argue that the rapid order of the D-dimer lab test really things off on the wrong foot. If the medical history was collected in the manner employed by the medical student in the end, a D-dimer study would likely have never been ordered. Once we learn these important details of the patient history, we realize that a pulmonary embolism really is not at the top of our differential for THIS particular presentation of “fainting spells”.

Similarly, borderline lab results often prompt us to take aggressive actions: in thinking about the D-dimer value seen in the workup above, in retrospect we can appreciate how the results seem out of proportion to the patient’s perceived presentation. If we believe that the patient has a pulmonary embolism so severe that it is causing her to faint, is a borderline positive D-dimer consistent with what we expect? There are always exceptions, however this lab value does not fully “fit” in the clinical picture painted by the team initially.

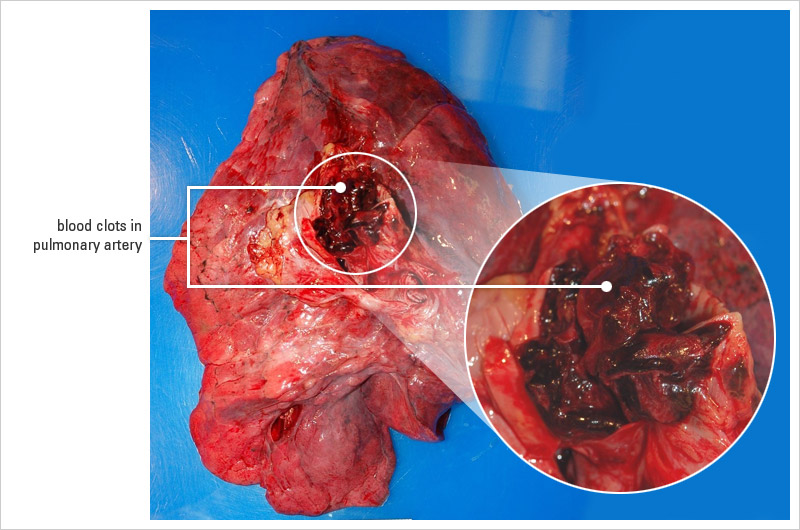

Is a small filling defect in the lung significant? In medicine we must also appreciate that given the frequency we scan patients will increase the frequency in which we find small incidental findings. Similar to the borderline D-dimer value reported, do we really believe such a small filling defect in the lung (such as the one found on the CT angiography of the chest) truly accounts for the patient’s fainting? Generally speaking this association is not the most intuitive one to make.

WHY SHOULD WE NOT THINK ITS COMPLETELY “CRAZY” THAT THIS HAPPENED?

While it seems odd that such a confusion could happen, we must appreciate that hindsight is of course always 20/20. The way the case is presented above ensures that everyone can see how suspicions for a PE are out of place, however IN THE MOMENT let us appreciate why one might consider a PE. If someone were to tell you that a patient with a recent surgery had a positive D-dimer, and that a CT angiography confirmed a filling defect would your mind not yell out PULMONARY EMBOLISM? This would probably be the correct answer on a standardized exam, so how can we break down each of these details and qualify who a PE is not likely?

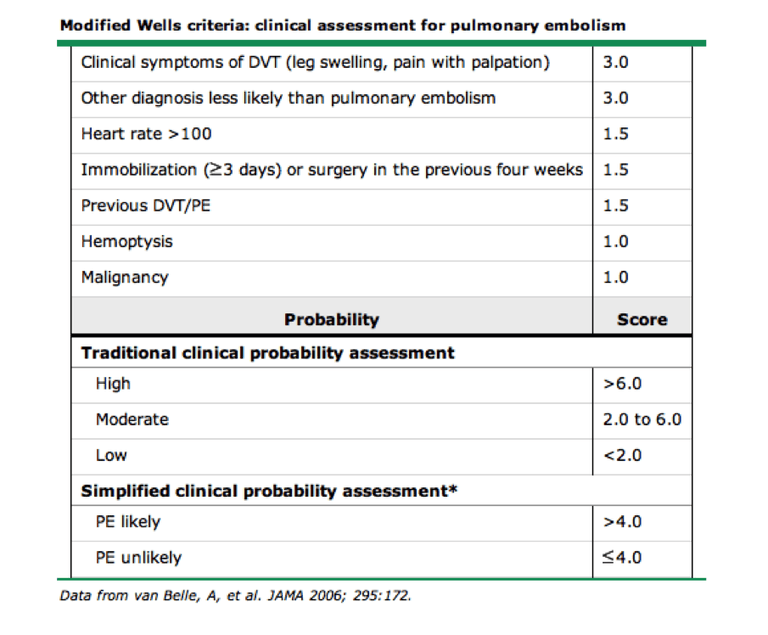

Previous surgery: a complication of a recent operation can often be DVT/PE. The issue in this case is that talking a look at the Well’s criteria (shown below) the patient’s history/physical actually did not support other risk factors that would give a Well’s score concerning for PE.

Positive D-dimer: if you don’t have perspective on how this test works (read more here) anytime it is positive you may assume a PE is likely! It is important to always try and take a step back and understand exactly lab tests CAN and CAN NOT tell us about the patient.

Filling defect on CT angiography: similar to the D-dimer study, if we do not understand the true significance of what the CT angiography is capable of telling us, we may misinterpret every filling defect detected as a serious issue! It is important to always ask one-self if the radiological “finding” can actually explain the patent’s presentation.

WHO CARES? WHAT WAS THE HARM IN WHAT HAPPENED?

While thankfully in this case the patient was not seriously injured due to the confusion, it is important to appreciate why we actually are even bothering to discuss this case! Here are some important points to consider:

- Compromised patient care: patients who recently have undergone surgery should not be put on heparin therapy unless it is absolutely necessary. While this patient only bled from her surgical sites for her breast reduction surgery, patients in other contexts may have more serous bleeds which can put their life in danger.

- Extended hospital stay: the more time a patient spends (unnecessarily) in the hospital the higher their rate of infection/development of other complications.

- Expenses: all the studies ordered have a financial cost associated with them. Whether it is the hospital, insurance companies, or even the patient, someone has to foot the bill of ordering a brain MRI on this patient (who arguably did not need this study during this visit).

- Time: everyone involved in the care of the patient (and the patient themselves!) will lose time the longer a workup drags on (and if unnecessary tests are ordered). This time could be put to better use in caring for other patients, and there is always a premium on time in medicine!

WHAT IS THE TEACHING POINT HERE? HOW DO WE AVOID THIS IN THE FUTURE?

As the medical student clearly demonstrated you must make sure you truly understand the chief complaint. Concerns for a pulmonary embolism (and the details of its workup and treatment) simply CAN NOT BE ALLOWED to compromise the history that is taken from the patient in the beginning. This is not to say that the history needs to be overly tedious and drawn out (quite the opposite). Because “fainting spells” can refer to a broad range of etiologies, it is the purpose of the medical interview to help narrow the scope of the patient’s workup. Most all of the issues above could have been avoided if the team had been aware of how this case was likely some type of presentation of orthostatic hypothenisoin and/or a vasovagal response.

Now in the end it is not clear based just on the student’s history physical what SPECIFICALLY is going on (what is the underlying etiology of the changes the patient experiences when standing?) however at the very least it should have steered the team away from pursuing the dead end that was the pulmonary embolism workup.

Page Updated: 09.20.2016