WHEN DO WE DO IT?

A pulmonary exam (even if abridged) is typically done for most patients. With this in mind, chief complaints that target the lungs as an area of interest (i.e. shortness of breath) can very well support the need to perform a more complete pulmonary exam.

COMPONENTS

A complete respiratory exam has a few key components that we will discuss in further detail below.

- Inspection

- Percussion

- Palpation

- Auscultation

INSPECTION

While perhaps a simple point, before begin any hands on aspect of your examination, it is important to inspect the patient properly visually. To begin with here are a few things to look out for.

- Respiration rate: how many breaths is the patient taking per minute?

- Is the patient using accessory muscles (such as those in the neck) for breathing?

- Is the patient cyanotic?

- Are there any scars indicating trauma or surgery? Make sure to learn the story behind every scar if possible!

- Are there any unique dermatological findings?

Furthermore, the below images are of possible findings that can be observed in some patients:

Accessory muscle usage: patients who have difficulty breathing may be using accessory muscles (such as those that can be seen in the neck) in order to aid with breathing.

Barrel chest: suggests hyperinflation in obstructive diseases such as emphysema.

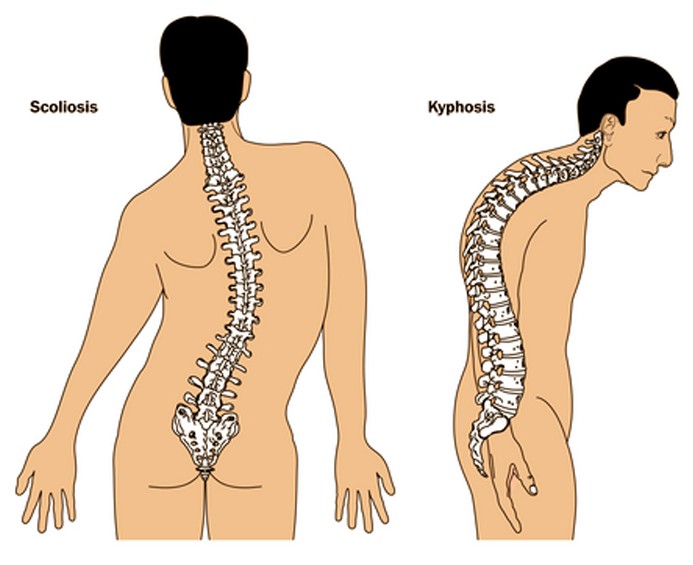

Kyphosis/scoliosis: these are abnormalities of the spine that can alter the dimensions of the chest cavity.

Nail clubbing: is the loss of the normal angle of the nail bed, and can occur in a variety of pulmonary conditions.

PERCUSSION

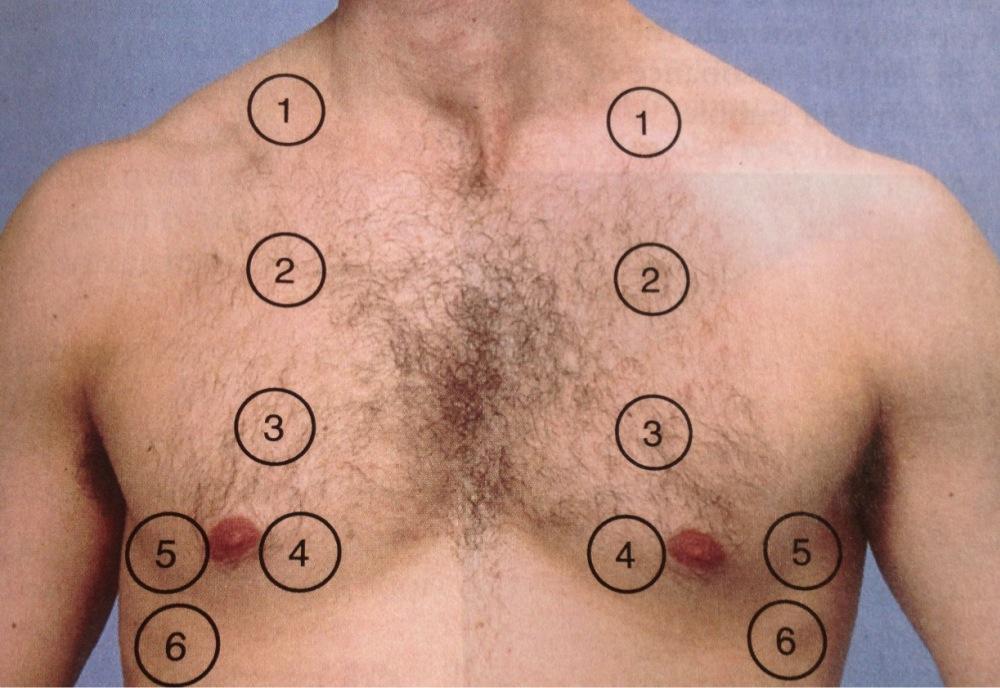

As seen in the abdominal exam percussion can be done over the lung fields to assess for tympanic changes that might be suggestive of the underlying pathophysiology of certain diseases (for example, plural effusion will be dull to percussion vs. a normal lung field). Below are the areas for both percussion and auscultation on the front of the patient.

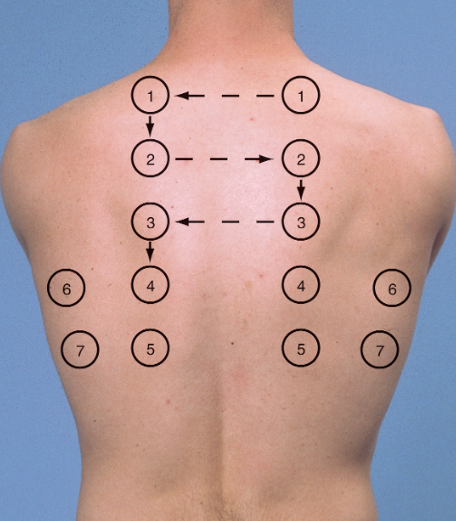

While here is the back of the patient (notice the scapula are spared).

Level of the diaphragm: When conducting percussion on the back of the patient, find the level of the diaphragm (where the dullness begins). Keeping this location in mind, ask the patient to take a deep breath and hold it while you find the new position of the diaphragm. In a normal individual (with a properly function respiratory system) the diaphragm should move ~5-6cm during inhalation.

PALPATION

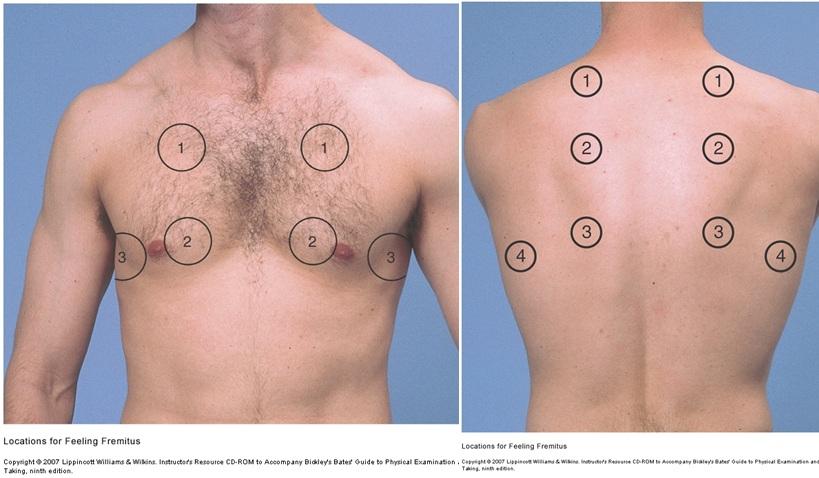

This portion of the exam will assess for “Fremitus” (palpable vibrations transmitted from the respiratory system to the chest wall as the paint speaks). As the patient says “99” put the ulnar surfaces of your palms bilaterally on the locations below and take note of increased/decreased fremitus. An increase in fremitus (above normal) is suggestive of consolidation within the lungs in the location of palpation (such as a lobar pneumonia). A decrease in fremitus below normal levels would be consistent with a pleural effusion, obstruction, or pneumothorax.

AUSCULTATION

Even before listening with your stethoscope, listen closely to how the patient is breathing (any odd sounds like wheezing present?). Using the locations above for palpations listen to the lungs of your patient taking note of:

- The presence of normal breath sounds (are any increased/decreased relative to what is expected?

- Are there any crackles, rhonci, wheezes?

*Essentially you are listening to hear for “anything odd”. The exact semantics of what each auditory finding is less important then the understanding that should you find something unusual, further investigation is warranted (i.e. a chest x-ray for a patient with crackles who very likely has pneumonia.

Page Updated 01.18.2016