Page Contents

- 1 WHAT IS IT?

- 2 WHAT CAUSES IT?

- 3 WHY IS IT A PROBLEM?

- 4 WHAT MAKES US SUSPECT IT?

- 5 HOW DO WE DO A THOROUGH CLINICAL WORKUP?

- 6 AT WHAT POINT DO WE FEEL CONFIDENT IN MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS?

- 7 WHAT ELSE ARE WE WORRIED ABOUT?

- 8 HOW DO WE TREAT IT?

- 9 HOW WELL DO THE PATIENTS DO?

- 10 WAS THERE A WAY TO PREVENT IT?

- 11 OTHER FACTS?

- 12 ARCHIVE OF STANDARDIZED EXAM QUESTIONS

- 13 FURTHER READING

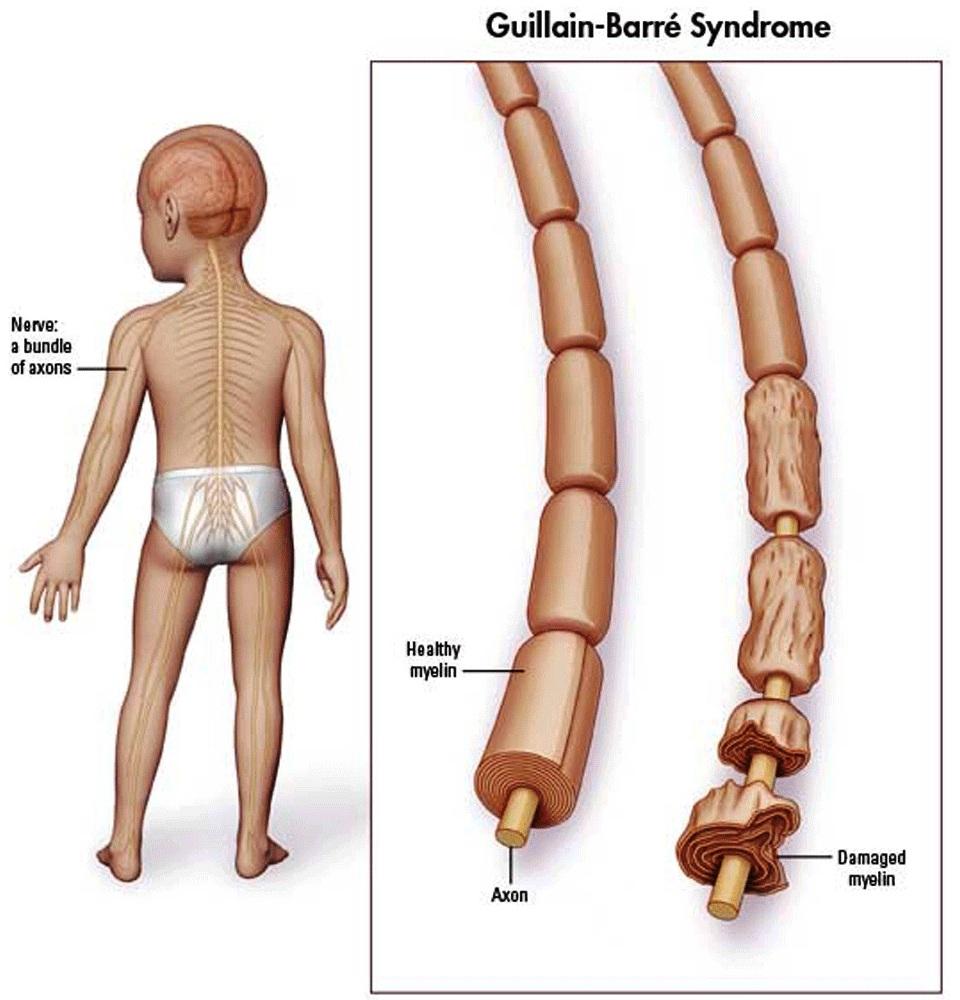

WHAT IS IT?

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) is a demyelinating disorder of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). It is an autoimmune type II hypersensitivity disorder. The most common subtype of GBS is acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy which is an autoimmune condition that destroys Schwann cells. This is a rare condition, however is worth understanding

WHAT CAUSES IT?

It is believed that this auto-immune condition is caused by infections that lead to an immune mediated attack of peripheral myelin (due to molecular mimicry, inoculation, and stress). While there are no definitive links as of now, the onset of GBS is often associated with recent infections. A very common infection preceding GBS is diarrhea caused by Campylobacter jejuni.

WHY IS IT A PROBLEM?

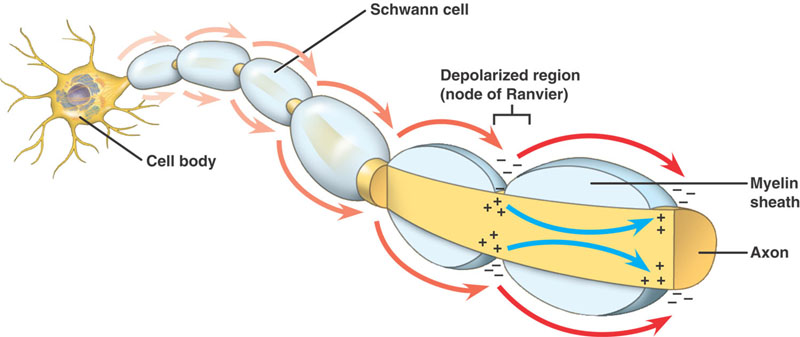

Schwann cells are responsible for myelinating PNS axons, and their destruction will lead to demyelination of these axons. This will in turn slow/stop nerve conduction (given myelin’s role in decreasing capacitance/promoting salutatory conduction). Ultimately patients will experience motor weakness and loss of sensation in their periphery.

WHAT MAKES US SUSPECT IT?

Risk factors:

Recent infections (Campylobacter jejuni, CMV, EBV, etc) often of the GI/respitory system

Initial presentation:

Chief Complaints:

- Tingling in hands/feet may be one of the first signs.

- Facial weakness: this is a very common issue in many patients.

- Muscle weakness: often affects the distal muscles first

- Bladder dysfunction is a common complaint that often occurs later on in disease progression.

History of Present Illness:

Past history of infection is common (as discussed above).

Onset of symptoms will be acute: symptoms develop/progress in days to weeks. This is very unique and can help raise suspicions for GBS.

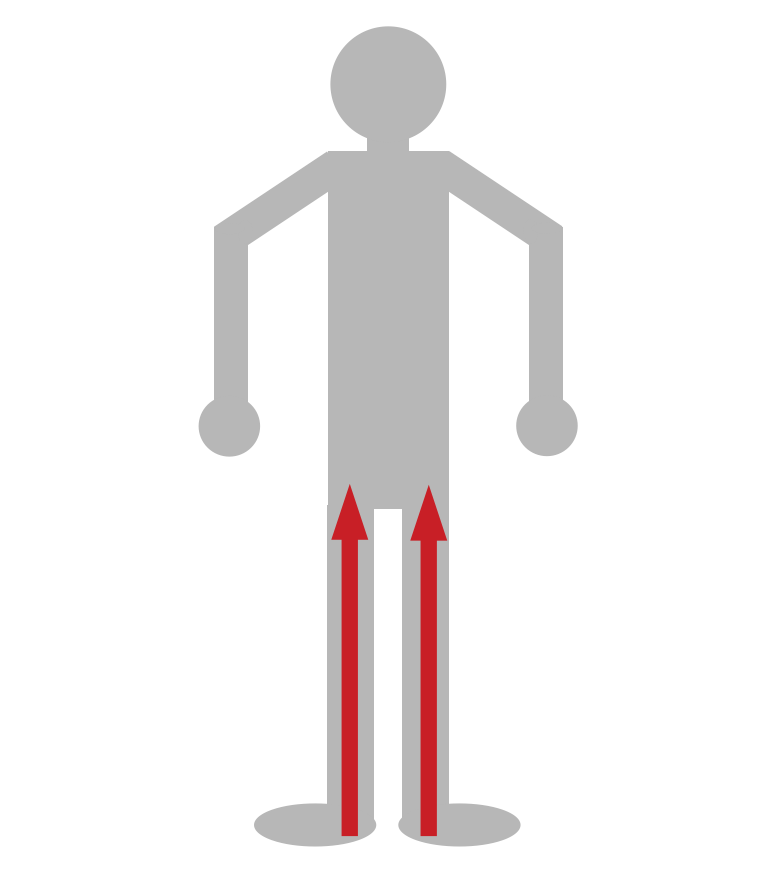

Motor weakness is often symmetrical in nature, and ascends progressively (distal lower extremities are affected first). This is becasue the longest axons that innervate the lower extremities are most sensitized to the loss of myelin (given the length the nerve impulse has to transverse).

Pain can be commonly felt by the patient in areas of weakness/sensory changes.

Bladder symptoms are generally not present at the onset of symptoms (but can develop over time).

Physical Exam:

Vital signs can show signs of autonomic dysregulation that can include:

- Cardiac irregularities such as bradycardia

- Wide blood pressure changes such as hypertension or postural hypotension

HEENT exam can demonstrate:

- Facial paralysis which is a very common finding in patients.

- Extra ocular muscle paralysis is also present (but less common then facial paralysis)

Respiratory exam can show shallow respirations. This may be caused by diaphragmatic weakness and is a serious sign.

Motor exam can show:

- Muscle weakness that is often symmetrical and ascending in nature

- Extent of weakness is variable depending on how advanced the condition is.

Sensory exam can also show patterns of altered sensation. It is important to appreciate that motor and sensory nerve fibers often travel together (sharing myelin sheaths as they can both contribute to the formation of a specific nerve). This explains why both neurological processes can be affected in demyelinating conditions such as GBS.

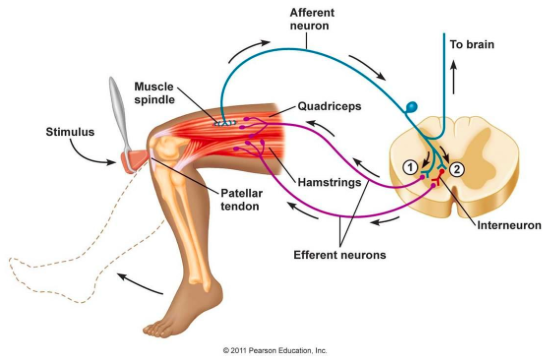

Reflex exam very often will show decreased reflexes (one of the earlier clinical findings of GBS) due to disruption of the reflex arc. Given the nature of the condition ankle and patellar reflexes commonly will be diminished first.

Fundoscopy can sometimes reveal papilledema in patients. The pathogenesis if not completely understood, however GBS can in some cases raise intracranial pressure in patients. This is a fact that is perhaps better learned for standardized exams vs. clinical practice.

HOW DO WE DO A THOROUGH CLINICAL WORKUP?

In light of a clinical history/exam that is suspicious for GBS there are a few other studies that can be performed that can help verify the suspected diagnosis of GBS.

Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis: evaluation of the CSF can help further support a diagnosis of GBS. It is important to note that an early lumbar puncture study may be completely within reference range, and a repeat study may be required to assess for the findings below.

- Xanthochromic (yellow) appearance of CSF due to high levels of protein.

- Increased protein (can be as high as 1 gram in some cases)

- Normal white cell count (albuminocytologic dissociation)

- All other values generally are in reference range: there should be no bacterial infection of the CSF if this is just GBS.

Nerve conduction studies/EMG will show prolonged distal latency and/or slowing of nerve conduction in the affected nerves.

Nerve biopsy (rarely indicated): if this study is done, it can provide histological evidence of immune mediated destruction of myelin.

AT WHAT POINT DO WE FEEL CONFIDENT IN MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS?

While there are papers dedicated to this topic (such as this one used by the NINDS) the major elements that strongly support a diagnosis of GBS are:

- Clinical presentation: symmetrical, progressive, and ascending pattern of weakness/symptoms that has an acute onset.

- CSF analysis: elevated protein with a normal cellular distribution white blood cells.

- Nerve conduction studies: demonstration of nerve demyelination (i.e. slowing of nerve conduction).

WHAT ELSE ARE WE WORRIED ABOUT?

Respiratory failure due to nerve demyelination: much like other processes within the body, respiration requires neurological control (ex. the diaphragm is innervated by peripheral nerves). As GBS progresses, the nerves that control respiration may become comprised, leading to the possibly fatal complication of respiratory failure. Pulmonary function testing can be used to assess the patient’s repository function.

HOW DO WE TREAT IT?

Treatment of GBS involves a few components that target the etiology and serious consequences of the disease:

Respiratory support is given to patients to protect their ability to oxygenate their body (patients may be intubated if necassary)

Pain can be controlled with medications such as Gabapentin.

Immunotherapy is administered to target the underlying etiology of this condition. The removal/inactivation of auto-antibodies that mediate the myelin damage is the goal of this therapy.

- IVIG is used to neutralize auto-antibodies in the blood. This treatment is generally recommended for less serious cases (where patients are unable to ambulate but do not require intubation)

- Plasma exchange is used to remove auto-antibodies from the blood of patients. This treatment is generally recommended for more serious cases (where patients require mechanical ventilation.

HOW WELL DO THE PATIENTS DO?

This is not a chronic condition: the majority of patients who are treated will survive this condition and recover completely after a few weeks/months.

WAS THERE A WAY TO PREVENT IT?

N/A: prevention methods are unclear given the mysterious etiology of this condition.

OTHER FACTS?

The endoneurium experiences an inflammatory infiltrate in GBS. This is the layer of connective tissue around the myelin sheath.

ARCHIVE OF STANDARDIZED EXAM QUESTIONS

This archive compiles standardized exam questions that relate to this topic.

FURTHER READING

Page Updated: 08.01.2016