Page Contents

OVERVIEW

This page is dedicated to providing a guide on the approach to interpreting an abdominal X-ray. This type of scan is also sometimes called a KUB (kidney, ureter, and bladder study).

This type of scan is often ordered given that it is fairly quick, easy, and cheap to obtain and can provide some insight regarding abdominal processes. With this in mind, it does have quite a few limitations, and often requires more follow-up imaging in order to more clearly identify pathology.

ORIENTATIONS USED FOR ABDOMINAL X-RAYS

Before delving too deep into the interpretation of abdominal X-rays, we must first learn about the different orientations in which the image can be taken. The orientations used for an abdominal X-ray include:

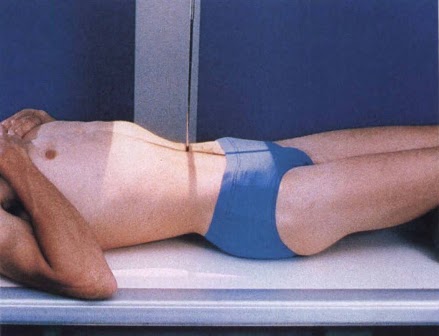

Supine: this is a common view that is taken which helps to assess for bowel dilation. These images are taken anterior to posterior.

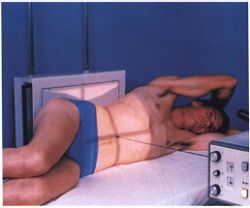

Upright: this second view can help visualize air/fluid levels, as well as any free air within the abdomen.

Left Lateral Decubitus Position: usually reserved for patients who are unable to stand, this also can help visualize air/fluid levels, as well as free air within the abdomen.

ANATOMY ON ABDOMINAL X-RAY

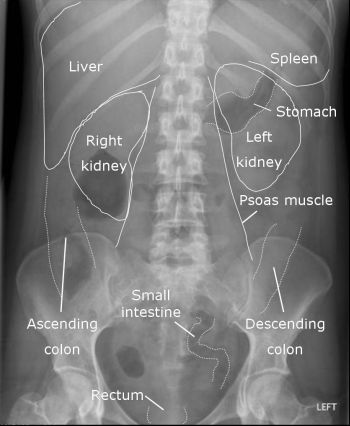

While not everything can be seen on an abdominal X-ray, there is a significant amount of anatomy that can be appreciated.

As a quick reference click on the links below to learn more about radiological anatomy as they relate to the below topics:

- GI tract: stomach, small intestine, large intestine

APPROACH (GECkoS)

Much like anything else, having an intentional approach to reading abdominal X-rays will serve you well. The acronym GECkoS can be used:

- Gas pattern (intraluminal): this refers to the gas pattern WITHIN the GI system

- Extraluminal gas: this refers to gas OUTSIDE the GI system

- Calcifications: areas that have increased density should be noted.

- Soft tissue masses: while not the most sensitive

GAS PATTERN (INTRALUMINAL)

The initial place to begin when evaluating a KUB is to evaluate the gas patterns within the lumen of the GI. There are a few clear pathological signs we are looking for here. The main things to keep in mind are if you are able to see any signs of either ileus or obstruction on the scan.

Localized ileus: this typically only involves one or a few loops of bowel. Bowel markings will be absent and that portion of the intestine can be dilated.

Generalized ileus: this will include all of the bowels (both small and large intestines). They will all be mostly void of any markings, and will be dilated/distended.

Small Bowel Obstruction: a common diagnosis (especially in a surgical context) an X-ray can reveal dilated loops of bowel, often with multiple air fluid levels.

Large bowel obstruction: these can appear quite impressive on X-rays given severe dilation of the small bowel.

EXTRALUMINAL GAS

Once characterizing the nature of gas distribution within the GI tract, we must evaluate if there is any gas outside of the GI lumen. There are a few important findings that one can notice:

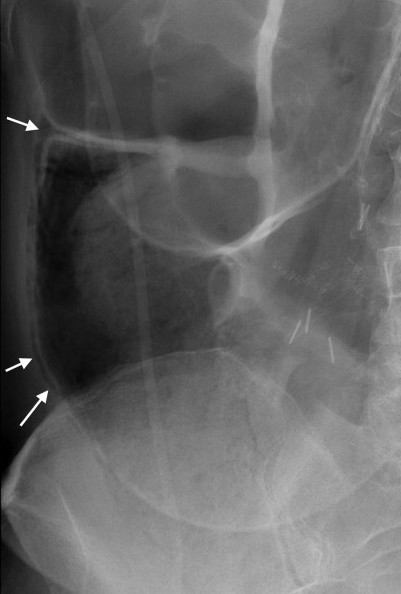

Pneumatosis intestinalis refers to the presence of gas within the bowel walls. It is highly suggestive for necrotizing colitis.

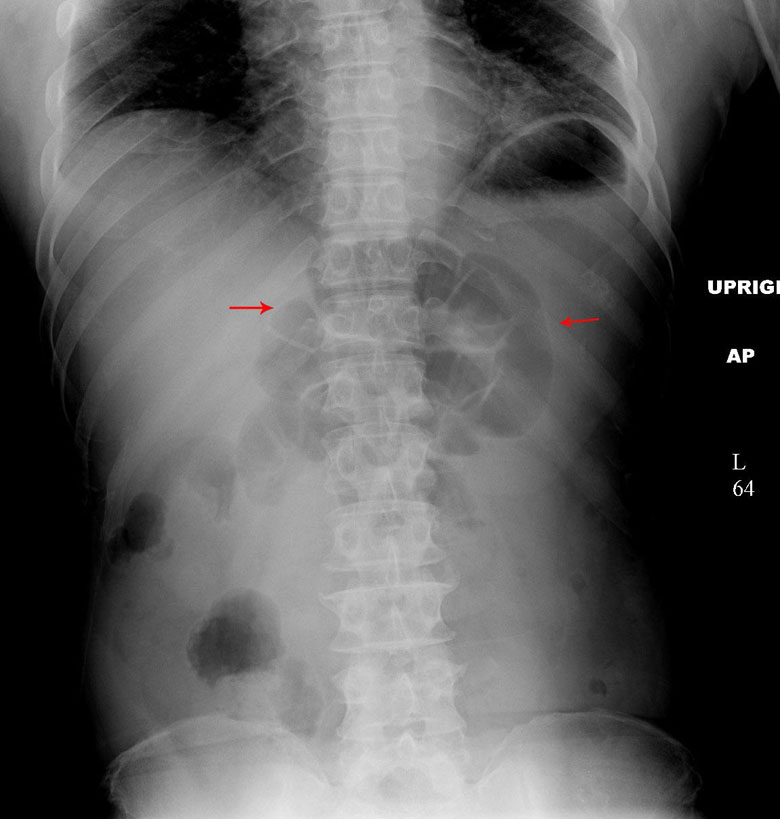

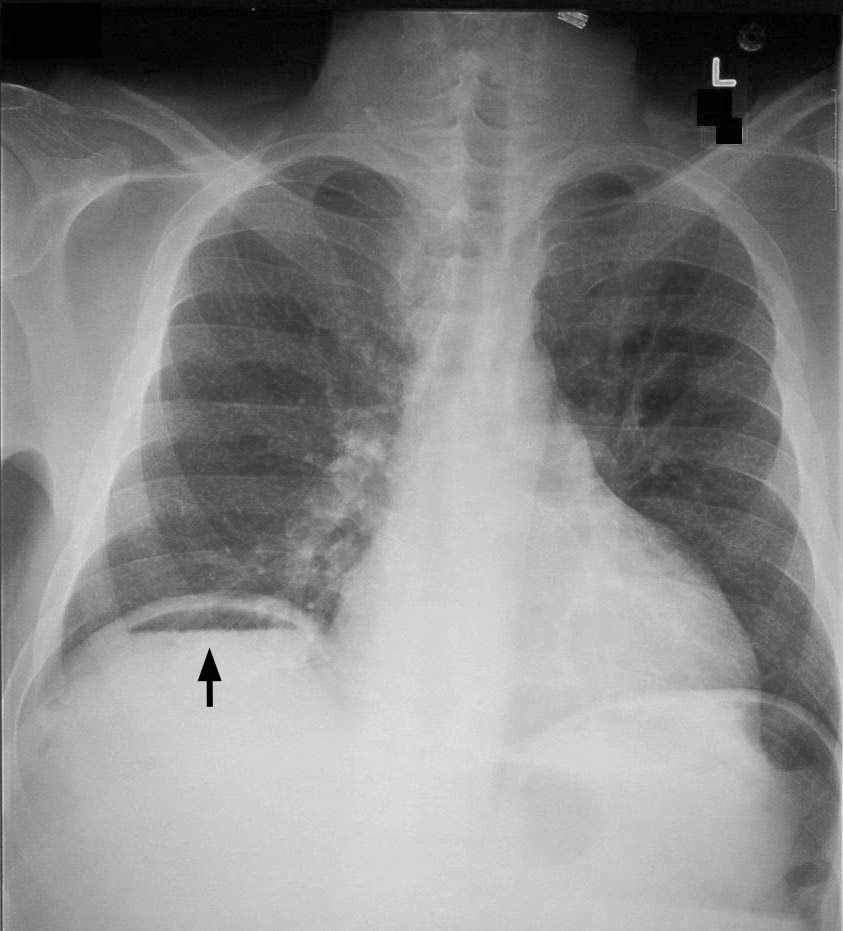

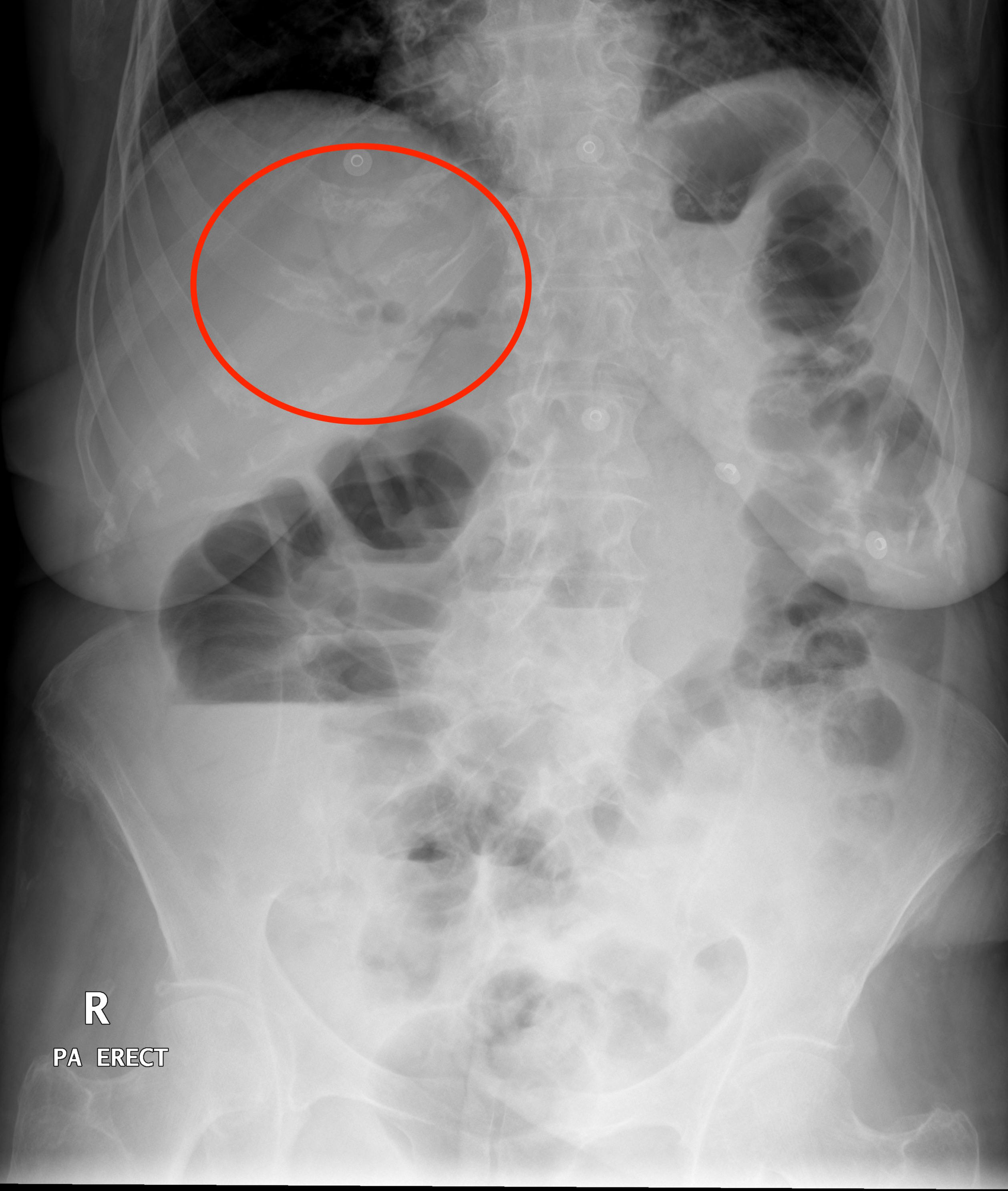

Air under the diaphragms (intraperitoneal free air): one of the signs of free air within the peritoneal cavity are collections of air under the diaphrams. This can be suggestive of processes such as bowel perforation.

Rigler’s sign (intraperitoneal free air): it is important to appreciate that free air can collect anywhere in the peritoneum (not just under the diaphragm). Rigler’s sign refers to the clear identification of both the internal and external borders of the bowel wall. Typically only the internal (luminal) border can be visualized however when air is also present on the outer surface of the bowel, the extraluminal border can also be seen clearly!

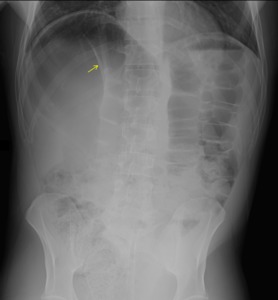

Falciform ligament sign (intraperitoneal free air): when air collects around the falciform ligament this can be visualized on an abdominal X-ray.

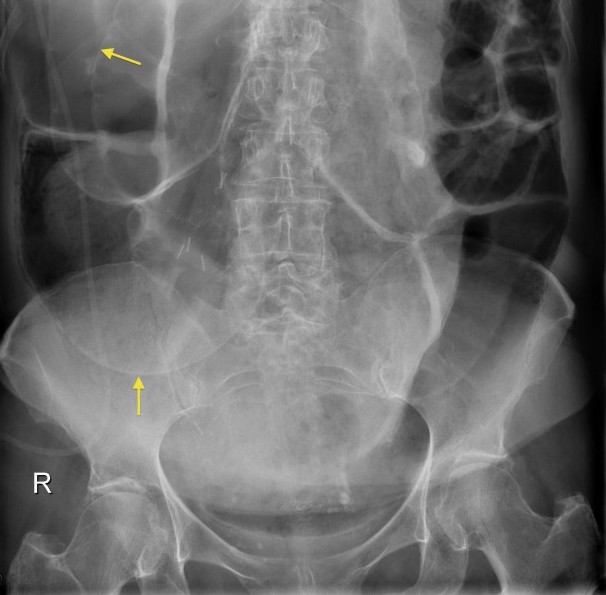

Portal Venous Gas: this finding refers to the accumulation of gas within the portal vein (or its associated branches. This is abnormal and the underlying pathology as to WHY there is air in the portal venous system is worth investigation.

Pneumobilia: this refers to gas within the biliary tree, and it can also be detected on a KUB.

CALCIFICATIONS

After all of the gas patterns have been assessed, the next step is looking for any calcifications/areas of hyperdensity on the X-ray. It is important to keep in mind that an abdominal X-ray is NOT the preferred imaging modality for detecting most calcifications, HOWEVER if it has already been ordered it should be analyzed for them irregardless. Follow up with other imaging modalities can always be done at a later time.

Gall stones: while ultimately ultrasound is the preferred modality for detecting gallstones, they can appear on a KUB as well. They will appear as calcifications in the anatomical location of the gall bladder/biliary tree.

Kidney stones: IV contrast CT is generally thought to be the best manner in detecting kidney stones, however these may also appear on a KUB (over the region of the kidney/ureter. They are hard to localize however given the difficulty of pinpointing the exact location of the calcifications.

SOFT TISSUE MASSES

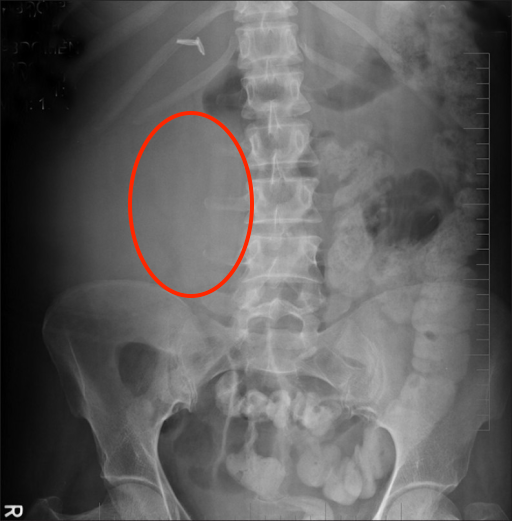

After all of the above has been done, one of the last findings to look for are any abnormal soft tissue masses. Again, the KUB is not necessarily the best scan for detecting these however once it has been ordered it still can provide some insight on whether or not these types of masses exist.

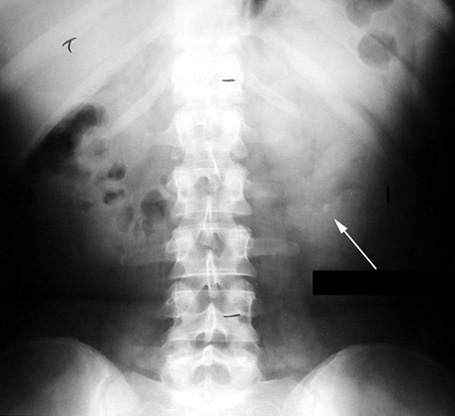

Look for abnormal tissue shadows and/or deviation of structures that could point the presence of a soft tissue mass.

Page Updated: 05.21.2016