Page Contents

- 1 OVERVIEW

- 2 HOW HAVE OTHERS APPROACHED IT IN THE PAST?

- 3 HOW ABOUT THE PRACTICAL APPROACH?

- 4 WHERE TO START AND WHY?

- 5 THE WORST CASE SCENARIO: UNDERSTANDING BROAD SPECTRUM COVERAGE

- 6 LOCALIZED INFECTION: DERMAL INFECTIONS

- 7 LOCALIZED INFECTION: PULMONARY INFECTION

- 8 LOCALIZED INFECTION: UTI

- 9 LOCALIZED INFECTION: MENINGITIS

OVERVIEW

This page is structured to serve as a practical guide to helping you learn (and apply your knowledge) about the different antibiotic medications. There are many medications out there, and it can be maddening to just even figure out HOW one should go about studying this facet of medicine.

HOW HAVE OTHERS APPROACHED IT IN THE PAST?

Granted that Stepwards is not the only group trying to teach antibiotics to others there are many different approaches to try and address this topic. Lets take a look at some of the approaches that some have tried in the past, so we can see where there is room for improvement.

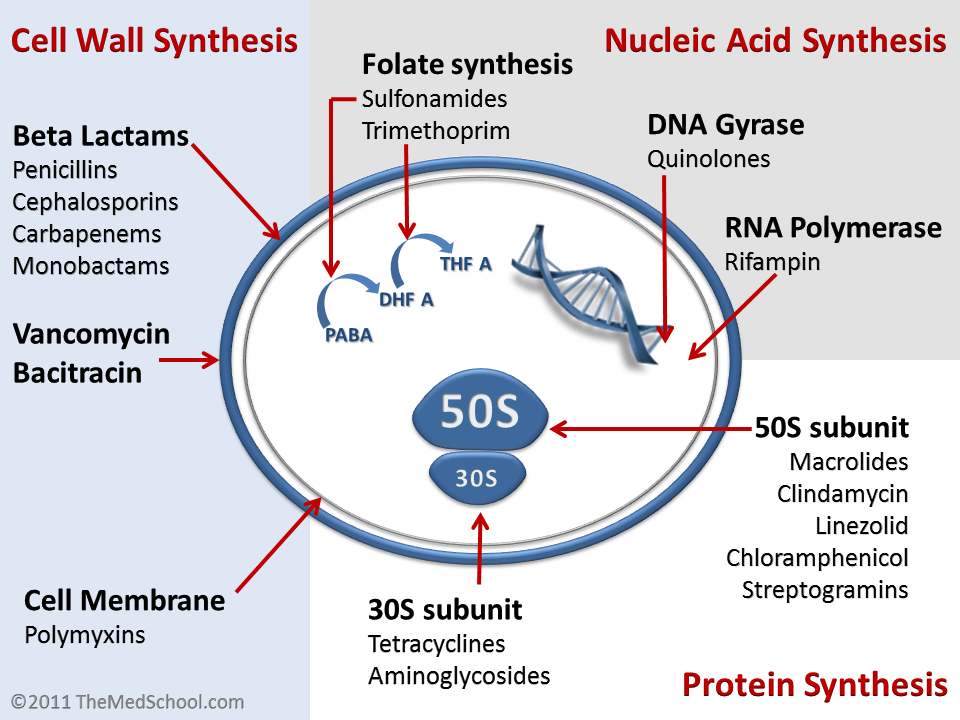

Learning medications by DRUG CLASS/MECHANISM: microbiologists are a big fan of this approach, and in many ways it makes a lot of sense. The mechanism of certain drugs will dictate their activity and which types of microbes they can cover. What this approach doesn’t allow for is appreciating that sometimes the mechanism is not clear/does not always perfectly explain the efficacy of medications.

Learning medications by MICROBE: some believe that learning the microbes is really the trick to learning the antibiotics, simply because the whole point of the medications is to treat specific bugs! There is a lot of value in this approach as well, because fundamentally it is true that the treatment should be tailored to the specific infection at hand. The challenge with only using this approach is that often in a clinical scenario the actual casual pathogen is unclear, and treatment often must be broad spectrum.

Learning medications by RANDOM MEMORIZATION/PATTERN RECOGNITION: this approach has become more popular with medical students as of late. The task seems so impossible, and there are so many standardized exams that test these random associations, that this approach has worked well for some. Their are now companies that will help facilitate that random pattern recognition based methodology of learning (such as by using elaborate cartoons). While its effectiveness in a test setting can be justified, it is important to appreciate that learning information in such a way renders it almost useless for real life clinical scenarios.

Other approaches (harder to classify): there are also other approaches that are taken that are a bit more difficult to classify. Take a look at this page dedicated to the concept of the Antibiotic Ladder.

HOW ABOUT THE PRACTICAL APPROACH?

There is no doubt that the above methods all have utility in their own way. Regardless, it seems as though there must be a better way in broaching the subject of antibiotics that perhaps incorporates the positives of the above methods, while addressing their individual shortcomings.

The approach here will be to simply mimic the clinical scenarios that physicians are presented with in an effort to teach antibiotic medications in a “real life” approach. Why learn something in a way that is not applied? The rest of this page will be dedicated to covering clinical scenarios that dictate our decision making. Lets see how this plays out!

WHERE TO START AND WHY?

Regardless of the approach, it can be difficult to decide exactly where to begin tackling this information. Especially in a clinically relevant context, we have to decide where to begin. Should we start going over lung infections? Cellulitis? Should we go from the most benign infections and work our way up?

Let us begin with the worst case scenario! Why? Simply because often times in medicine we are faced with uncertainty and HAVE to prepare for the worst case scenario in order to preserve the health of our patients. This will help us review our strongest antibiotics, and also we can understand what our most aggressive treatment options are (and work backward while making our reasoning at each step of the way clear).

Why is the worst case scenario more common then we might expect? It is very important for us to appreciate the limitations of our clinical studies in deciding definitively where an infection is, and what is causing it. Here are some important points to remember from real life:

- Bacterial cultures take time! It can take days to grow out (and correctly identify) bacteria from blood, CSF, urine, etc. There are very few cases where antibiotics will be started AFTER culture results are returned.

- Bacterial cultures often get contaminated: because our skin is covered in bacteria, it can be common for bacterial cultures to become contaminated (and effectively useless). Once we learn that this has happened, at that point patients are already on antibiotics, so repeat cultures may come back negative (because the pathogen may no longer be easy to detect).

- Cultures may not identify a single pathogen: lets say we take a surface wound culture and our cultures grow out pathogens that we KNOW colonize the surface of the skin of most patients. How is this helpful? We are not given any new information with this culture….and find ourselves in the same position as when we started.

THE WORST CASE SCENARIO: UNDERSTANDING BROAD SPECTRUM COVERAGE

To set the stage for the worst case scenario let us take a patient who has unstable vitals with suspicions for sepsis (patient is SICK), we don’t have a source for infection (our clinical studies are pending), and we need to begin treatment NOW. What do we do? What are our hardest hitting options? In this scenario (especially when the patient’s life is in in danger) we must begin treating empirically with broad spectrum coverage. This is because all we have at this point is a suspected infection with no source/or suspect pathogen.

Vancomycin with Zosyvn: this is a very popular antibiotic combinaiton for patients who have an unknown source of infection. Lets take a closer look at why this option is an attractive one:

Vancomycin (given its activity in inhibiting cell wall synthesis) will help cover against many different gram positive organisms. This medication is useful in covering for MRSA which is not covered by Zosyvn.

Zosyn (as a combo ß-lactam and ß-lactamase inhibitor) helps to cover for some gram positive bacteria, but also has excellent anti-aerobic activity.

LOCALIZED INFECTION: DERMAL INFECTIONS

In the setting of a suspected dermal infection let us discuss an intentional approach to picking the right antibiotics for treating the patient in question.

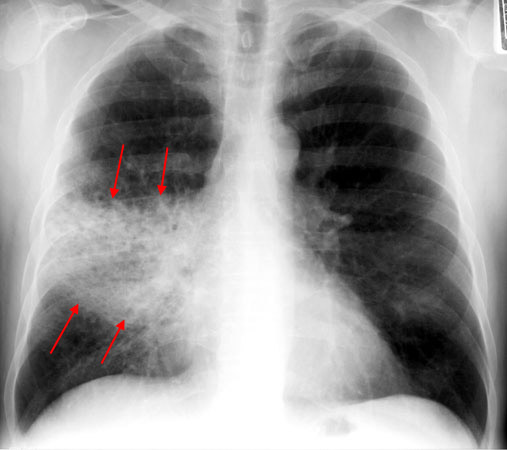

LOCALIZED INFECTION: PULMONARY INFECTION

In the setting of a suspected pulmonary infection let us discuss an intentional approach to picking the right antibiotics for treating the patient in question.

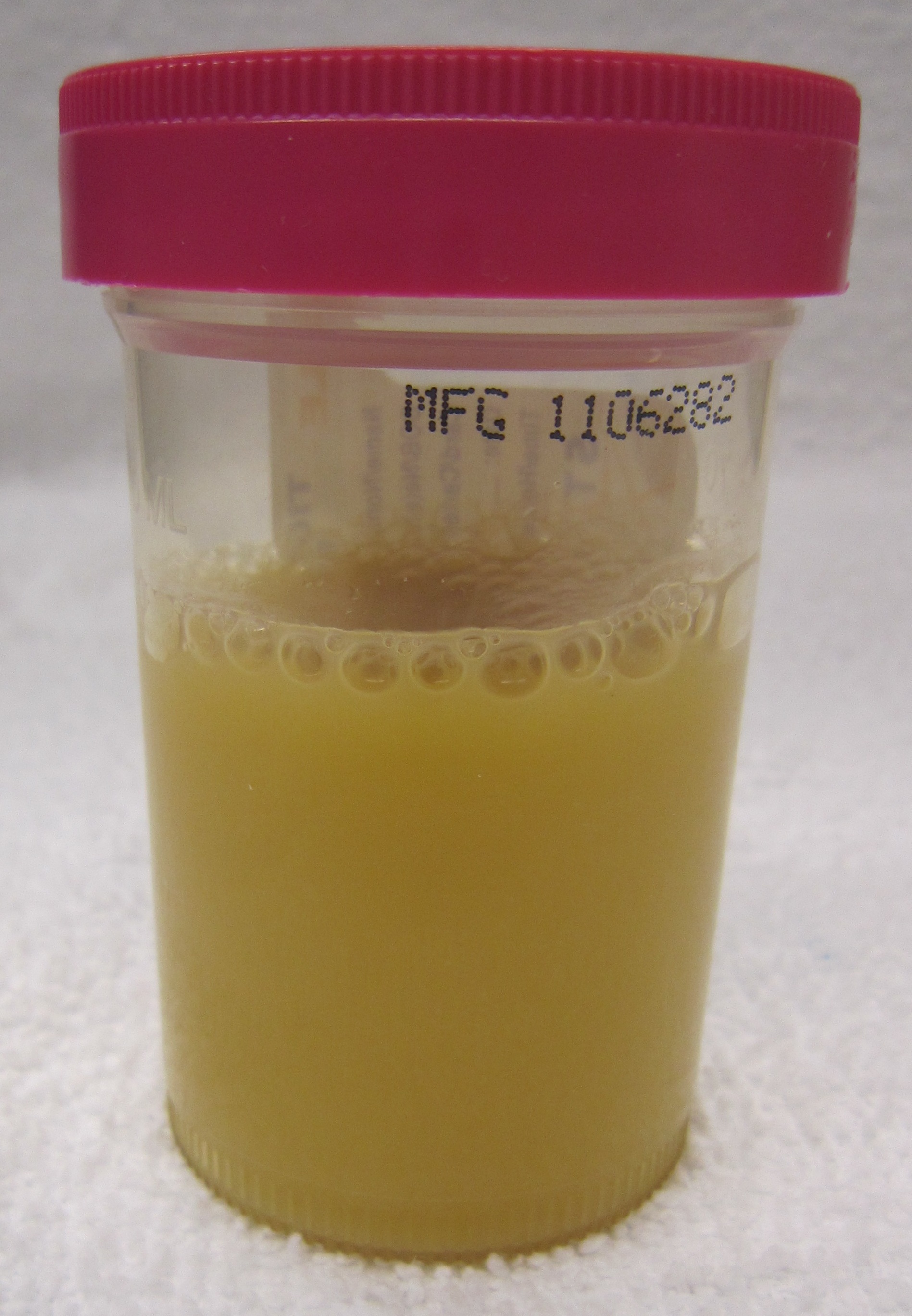

LOCALIZED INFECTION: UTI

In the setting of a suspected urinary tract infection let us discuss an intentional approach to picking the right antibiotics for treating the patient in question. Read about this here on the Guide To Treating Urinary Tract Infections.

LOCALIZED INFECTION: MENINGITIS

In the setting of suspected meningitis let us discuss an intentional approach to picking the right antibiotics for treating the patient in question.

Page Updated: 08.09.2016